KHARTOUM – The protesters always wanted their rally to be peaceful, they said. But by the end of the day at the gold mine in Sudan’s remote Wadi Alsingair region, one man was dead and five more injured.

The workers had gathered at the site, 400km north of Khartoum, to protest against a government deal in October that assigned mineral rights to Russian company Miro Gold.

The mine is in a small valley inhabited by a few thousand residents who are without access to hospitals, schools or properly maintained roads. What little arable land there was is now mostly used for mineral extraction.

The Russian guards included a sniper, supported by the Sudanese police, who suddenly fired on us without prior warning

– Ahmed Alsaim, proteste

Ahmed Alsaim, one of the protesters, told MEE that the land belongs to them and that they demonstrated peacefully because they had not been consulted before work began.

“The Russian guards included a sniper, supported by the Sudanese police, who suddenly fired on us without prior warning,” he said.

Al-Habob Farah, 28, one of the protest leaders, was killed. Alsaim says he was singled out and blamed the River Nile State, in which the mine is based, for not defusing the tension.

Hatim Alwasila, the state governor, denied that the Russian guards opened fire at the protest on 5 March.

“The police force at the site was responsible for protecting the company and its staff,” he said. “They tried by all means to avoid using their power, but the locals started to attack the company, so the police enforced their powers.”

Middle East Eye contacted Miro Gold but it had yet to respond at time of publication.

The race for land

The death of Farah and the involvement of a foreign company sparked anger across Sudan, drawing criticism from opposition politicians and activists.

Some compared it with US private security firm Blackwater, since 2011 known as Academi, whose employees killed 14 Iraqi civilians in Baghdad in 2007.

One Twitter user called Mosab Martin posted images of a man alleged to be the guard raising his rifle as well as of the dead and injured.

He wrote that “an immediate investigation should be opened, the Russian company should be expelled from the area, or otherwise we will see the blood everywhere in the River Nile state”.

The death and protest also reignited debate about who owns the rights to natural resources in Sudan, as Khartoum intensifies its efforts to attract external investors.

Sudan is poor: its estimated GDP per capita in 2017 was only $1,428 – less than a quarter, for example, of Jordan’s. The inflation rate for the same period was 26.9 percent, placing it 222nd out of 227 territories and below Syria and Yemen.

Yet Sudan is rich in resources: the tragedy is how ownership of these has often fuelled conflict.

Internationally, Khartoum is in a decades-long dispute with Egypt over the Halaib Triangle to the north of Sudan, which has been run in effect by Cairo. The region is rich in minerals and oil: in January 2016, Sudan put its forces on standby as tensions increased.

In 2017 the country produced 107 tonnes of gold, compared with 93 tonnes in 2016, making it the third-biggest gold producer in Africa after South Africa and Ghana. Those figures are likely an under-estimate and do not account for gold produced illegally.

Disputes over land are traditional: historically they have occurred during the dry season, as nomads, seeking fertile lands on which to graze their cattle, come into conflict with farmers. Usually such tensions are resolved through tribal negotiations.

But land ownership laws in Sudan are not clearly defined. In some parts ownership is defined under laws issued by the British colonial administration but for the most part it is defined by centuries-old custom between tribes and community leaders.

Government intervention has exacerbated the situation during the past two decades, most notably in Darfur. There, Khartoum backed Arab nomads in a land conflict that spiralled into ethnic clashes and then a war that has left at least 300,000 people dead and at least 2.7 million displaced.

The conflict resulted in international sanctions against Sudan, which were lifted only last October. In March 2017, former financial minister Badr Eldin Mahmoud put the cost of 20 years of sanctions at $45bn.

The economy was also badly hit when South Sudan became independent in 2011, taking three-quarters of the country’s oil revenue with it. Currently it is undergoing severe austerity as part of an economic reform plan in line with International Monetary Fund (IMF) recommendations

The result: Khartoum has to rely even more on external investors exploiting natural resources to maximise its income.

Disputes have erupted between the government and landowners over dam construction in northern Sudan, including at the Marawi dam in March 2009. The dam is being built through loans from China, Saudi, Oman, Abu Dhabi and Kuwait among others. Construction of the Dal and Alshiraik dams, for which Saudi Arabia is supplying grants, has been delayed due to protests.

Four people were killed in 2007 when landowners protested against the construction of the Kajbar damnear the border with Egypt.

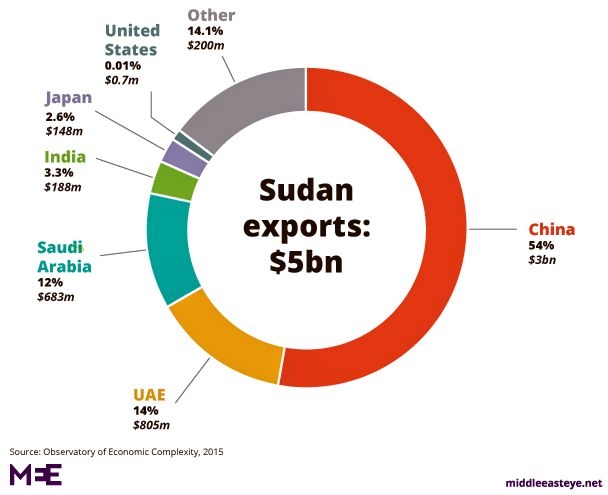

Khartoum has tried to make international alliances where it can, most notably with China, which takes more than half its exports. In December 2017, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said the two countries aimed to eventually boost two-way trade to $10bn.

But it is gold which offers the biggest opportunities. There are 170 gold mining companies working in Sudan, although this does not take account of unofficial mine operations.

Khartoum plans to raise production in 2018 to make the country the ninth-biggest producer in the world and the second-biggest in Africa.

Power and corruption

But promises of future trade are of little comfort to the gold workers of Wadi Alsingair. Abdullah Mohamed, a community leader, told MEE that the tension began when the government signed the deal with Miro Gold.

“We met the governor of the state and raised our concerns,” he said. “We have been mining in our area for 10 years. The contract with these investors will inflict big losses on us.

“The governor promised to consult us before the company began working, about compensating us. But surprisingly, the authorities have allowed the company to begin working, bringing their equipment and even expelling the local miners from the area.”

The government, Mohamed said, was more concerned about foreign investors than about its own citizens.

Oshiek Mohamed Tahir, the minister of state at the Ministry of Minerals, told MEE that the government was keen to guarantee the interests of the citizens “but within the laws”.

But last year the US-based Enough Project said in its report “Sudan’s Deep State” that the country’s federal and local elites and armed groups commit “acts of violence that result in the dispossession of local populations”.

“Revenues from oil, gold and land allocation in Sudan are often affected by conflict. An inner circle within Khartoum has privately expropriated oil, gold, and land for self-enrichment and to maintain control through corruption and violence.”

The Sudan Democracy First Group (SDFG) has previously warned that incidents of clashes over land, between the government and the local owners, have sharply increased during the past few years, leading to the deaths of dozens of locals.

Alshafia Khidir, the author of The Tribe and Politics in Sudan, said that Sudanese elites are using the power of the state and allying themselves with local and international investors to loot the lands of the locals.

The government is using the laws to confiscate the lands of the small farmers, traditional owners and nomads in favour of the investors

– Alshafia Khidir, writer

“The government is using the laws to confiscate the lands of the small farmers, traditional owners and nomads in favour of the investors.”

He said that this had led to the collapse of the agricultural sectors, such as the El Gezira scheme, once one of the world’s biggest irrigation projects and responsible for much of biggest areas for cultivating cotton in Africa.

It failed when the government focussed too much on oil and sidelined agriculture, privatising irrigation services and the provision of seeds. A strategy to grow more wheat, which fails to thrive in hot climates, also flopped.

“With the economic deterioration and the appearance of oil and gold, the traditional conflict over resources and wealth in Sudan has reached an advanced and serious point.”

The risk of gold

Mohamed Salah, a researcher in the socio-economic and environmental impact of gold mining in Sudan, told MEE that the desire to increase gold mining carries two inherent risks.

The first was that the government, by making deals with outside investors, was pitting itself against locals.

The use of mercury and cyanide in the purification process makes miners more vulnerable to respiratory diseases and cancer

– Mohamed Salah, researcher

“Accordingly, the government has no choice but to defend the interests of the investors,” he said, “using the power of the state to confiscate the land through many tricks including changing the law.”

The second, Salah said, was environmental and the processing of gold, one of the main sources of mercury contamination in Africa.

Fine particles from the processing of gold pollute water and air, becoming a serious health hazard if inhaled by humans and animals. The most common use for mercury is in small-scale mining operations, according to Human Rights Watch.

Salah said: “The use of mercury and cyanide in the purification process makes miners more vulnerable to respiratory diseases and cancer.”

In November 2017, one person was killed amid protests in Kologi, South Kordofan, against gold mining companies using toxic chemicals, according to local media.

Translation: A student was killed and others wounded when shots were fired at a demonstration against gold companies in Kologi, South Kordofan

The protests are likely to continue. Abdul Majeed leads a coalition representing land-confiscation victims in the Khartoum suburbs of Aljiraif, Alshajara, Alhamadab and Alhalfaya, using protests, meetings and sit-ins to get their message across.

In recent years the group has attracted support from those impacted by dam-building projects in the north of the country. Now it’s gold-mine workers.

The opening of the hydro-electric dam on the Nile River at Merowe, north of Khartoum, on 3 March 2009 (AFP)

The opening of the hydro-electric dam on the Nile River at Merowe, north of Khartoum, on 3 March 2009 (AFP) Majeed sees the incident on 5 March as evidence of a remarkable deterioration. “Look at the general causes of conflict in the country. We find that land disputes are the main subject of the trouble, from Darfur to the Nuba Mountains to the Blue Nile, with conflicts over oil, gold-rich areas, dam locations and other issues.”

He called on landowners, regardless of their backgrounds or jobs or interests, to rally together against the alliance of foreign investors and government.

“We call on the all victims from land confiscation across the country to unite and organise themselves in one body to defend their history and identity.”